The Best Books of 2022: Science Fiction & Fantasy!

/Best Books of 2022: SFF!

For the last few years at least, the events of any morning’s newsfeed have seemed to handily outpace most science fiction in terms of technology and most fantasy in terms of Dark Lords, which didn’t necessarily obviate the latest offerings of the genre but did sometimes serve to highlight the lazy rhetorical conventions and shrill political cant of those offerings – both to the point where reading a new work of sci-fi or fantasy often felt like more of a duty than the illicit thrill it always was in past decades. The giants seemed tired, the newcomers seemed compromised, and far too much of the genre seemed pointless. But there were exceptions! These were the ten best of them:

10 The Starless Crown by James Rollins (Tor) — James Rollins returns to his epic fantasy roots in this stereotypical but hugely energetic first installment about a Girl Who’s the Key to Everything who assembles an Unlikely Fellowship around a Mysterious Macguffin in order to save the world. The whole thing would sink instantly under the weight of its own cliches if it weren’t for the zest Rollins brings to the telling, amply aided by the pacing and plotting skills he’s learned from decades of writing thrillers for a general readership.

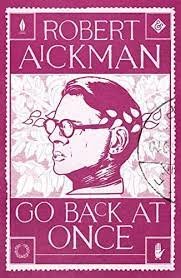

9 Go Back At Once by Robert Aickman (And Other Stories) — This stylish reprint of a strange, quirky book about two young women finding layer upon layer of unexpected (and unwanted) revelations in a secretive utopian community was one of the biggest surprises the publishing world had for me in 2022. Aickman wrote this odd book half a century ago, but virtually every one of its distempered obsessions seems to speak directly to the 21st century, God help us.

8 Last Exit by Max Gladstone (Tor Books) — Max Gladstone’s latest fantasy, the story of a Girl Who’s the Key to Everything who assembles an Unlikely Fellowship around a Mysterious Macguffin in order to save the world, has all the hallmarks of this author’s zippy writing style: sharply drawn characters, lavishly-imagined world-building, and particularly irresistible pacing. Gladstone also has a tendency to center his ensemble casts around one stand-out character, and in Zelda, readers will delight in that character here.

7 Engines of Empire by RS Ford (Orbit) – Ford’s sprawling novel is filled with prominent and very well-drawn characters dealing with upheavals afflicting the nation of Torwyn and its all-powerful guild. Two main characters, heirs to the most influential of those guilds, are sent on seemingly very different independent missions that turn up separate but ultimately converging shocks for the realm. There’s a refreshingly pragmatic undertone to much of Ford’s world-building; it pulls the reader directly into the stakes of the story.

6 The Stars Undying Emery Robin (Orbit) – In Emery Robin’s story of a Girl Who’s the Key to Everything assembling an Unlikely Fellowship around a Mysterious Macguffin in order to save the world has a fascinating bit of innovation and a very inviting bit of relationship-building at its heart. Robin employs a pleasing variety of narrative techniques to tell various facets of a tale about two young heroines who are plugged into a network beyond the understanding of their world as they contest with each other and an array of other forces to gain power.

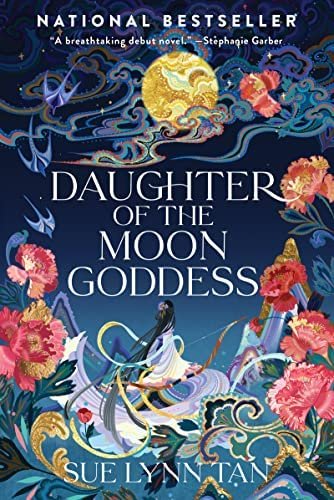

5 Daughter of the Moon Goddess by Sue Lynn Tan (Harper Voyager) – Sue Lynn Tan’s debut fantasy story of a Girl Who’s the Key to Everything assembling an Unlikely Fellowship around a Mysterious Macguffin in order to save the world is crafted out of Chinese mythology rather than European folklore: Xingyin, the daughter of the moon goddess, must hide her supernatural abilities by taking on a disguise in the Celestial Kingdom, where an array of ordinary human experiences, wonderful to her, unfold in ways that are genuinely touching.

4 Rise of the Mages by Scott Drakeford (Tor) – This next entry, also a debut, Scott Drakeford firmly establishes himself as a formidable talent in the grim-and-gritty neighborhood of epic fantasy, telling the story of a man who responds to the instructions of his clandestine mage-tutor in order to become a power in his own right – not only to combat an ancient rising evil but also to save the life of his brother. Drakeford has a gift for stuffing his narrative full of details without making it feel stuffed, and his skill at pacing keeps the book hurtling along after the second act.

3 This Woven Kingdom by Taharef Mafi (HarperCollins) – This novel, YA in its structure and sentiment, is likewise drawn from a non-feudal, non-European folkloric matrix, in this case Persian mythology, and the story it tells, of a Girl Who’s the Key to Everything assembling an Unlikely Fellowship around a Mysterious Macguffin in order to save the world, is full of the teased passions and overblown wordplay of young adult fiction but also its vivid primary colors, making this a promising start to a new series.

2 In the Shadow of Lightning by Brian McClellan (Tor) – Brian McClellan’s terrifically high-energy story of a fallen outcast who must claw his way back from rock bottom in order to avenge his mother’s death is working familiar territory, admittedly, as are most of the entries on the list this year, but as with most of those other cases, McClellan attacks those old gimmicks with a vigor that makes the book feel fresh.

1 The Citadel of Forgotten Myths by Michael Moorcock (Gallery/Saga Press) – In a comparatively weak year for science fiction and fantasy, it feels almost unfair that Michael Moorcock should wade into the competition at all, much less that he should do so with a return to his most popular creation. And yet that’s just what happens in this, the year’s best SFF entry, a new story in Moorcock’s much-honored saga of Elric of Melniboné, set in the early years of the doom-haunted albino sorcerer’s adventures. Moorcock has lost scarcely a stroke of his narrative power in his early eighties; as a result, far from merely holding a place on a list, The Citadel of Forgotten Myths immediately takes its place in the canon.