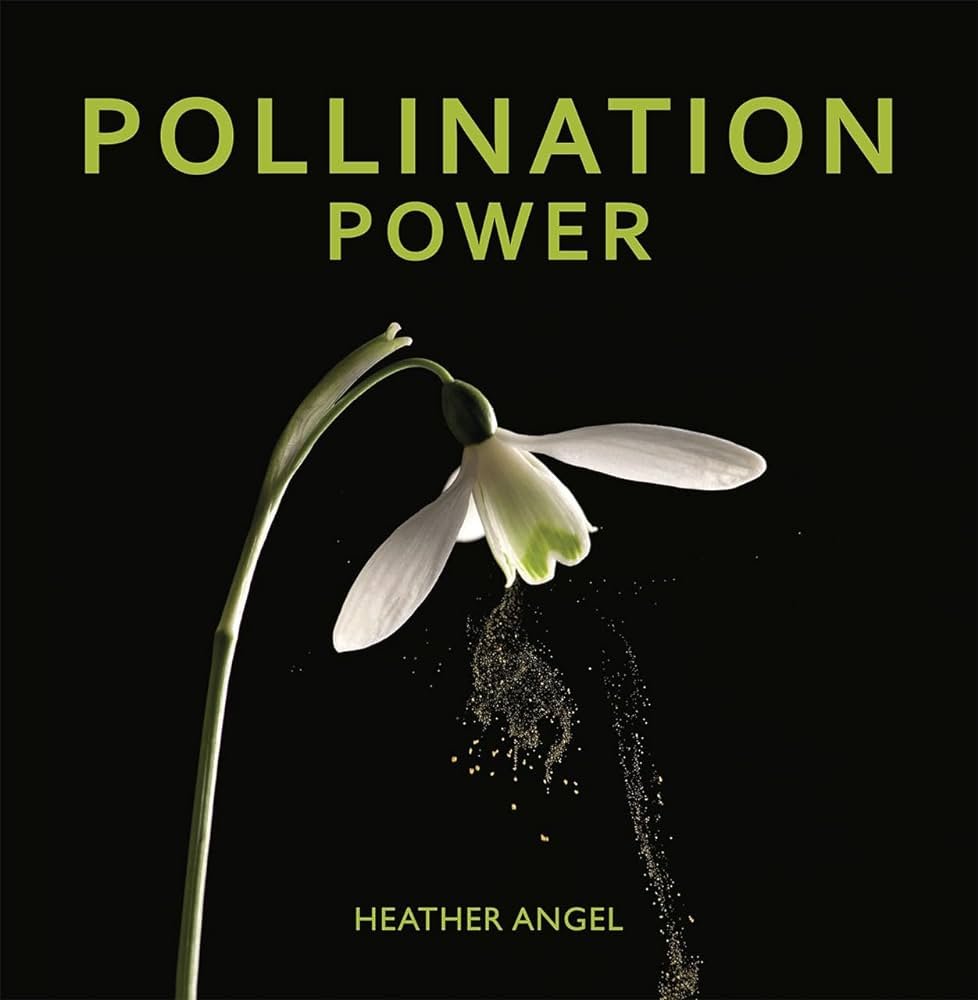

Book Review: Pollination Power

/by Heather Angel

University of Chicago Press, 2016

Over three quarters of all plants rely on animals to transport their pollen, wildlife photographer Heather Angel tells readers at the beginning of her new book Pollination Power, a sumptuously-produced picture book from the University of Chicago Press. It's this massive, complicated, delicate network that constitutes an invisible vascular system for all land-life on Earth, and it's Angel's subject in these pages. She took her camera and her keenly observant eye to locations as far-flung as the Cape of South Africa, China, South America, the Royal Botanic Garden at Kew, and her own garden in Surrey, and the resulting album is a fascinating look at a world most people never see in such detail.They see it in some small detail, of course. One of the most rewarding spectacles of the summer seasons in most parts of the world is the endless toiling of bees in fields, flitting from flower to flower and settling down over and over to a total concentration on their work. Pollination Power lays open some of the mysteries of that work in dozens of lovely, highly-detailed photos accompanied by plenty of helpful annotations:

Honeybees, bumblebees and orchid bees collect pollen and transfer it to the pollen baskets on the hind legs. Other bees, as well as flies, hoverflies and wasps, carry pollen on their hairy bodies. Birds carry pollen on their feathers, bills, and even on their feet, while mammals carry it usually on their muzzle fur as they reach inside a flower for the nectar. Perhaps the most bizarre place for pollen pick-up is on the tip of the tongue of lesser double-collared sunbirds (Cinnyris chalybeus) when they feed on the red, scentless flowers of the climber Microloma sagittatum in South Africa. No insects visit the flowers that fail to fully open, but pollen is transferred in pollen-packed sacs known as pollinaria.

These annotations are present mainly as addenda to the photos; if Pollination Power has a systemic flaw, it's the degree to which the wonder of the book's images takes precedence over the pedagogical aspect that's usually front and center in nature studies like this. In many of the text sections, readers get passages of explanations that are unfailingly interesting but can sometimes veer into technical terminology that's less carefully specified than it otherwise could be.

Beetles are the most prolific insect group and they pollinate many more flowering plants than any other invertebrate pollinator. These insects are important pollinators in tropical and arid areas and in South American cloud forests they make up 45% of all pollinators. Many use flowers as places to meet and mate. Detailed studies on some beetle-pollinated flowers reveal beetles are not the primitive pollinators once thought and their visitation to some flowers are controlled precisely by the flower itself. For example, Magnolia grandiflora attracts beetles by emitting a lemony scent specifically when the female phase is receptive. The flowers then close, trapping the insects overnight and reopen the following morning after the anthers have dehisced, so the beetles depart carrying a pollen load.

But as is clear from this and many other passages, Angel's glowing enthusiasm overcomes any tendency she might have toward wonkishness. Even readers whose anthers haven't yet dehisced will enjoy it.