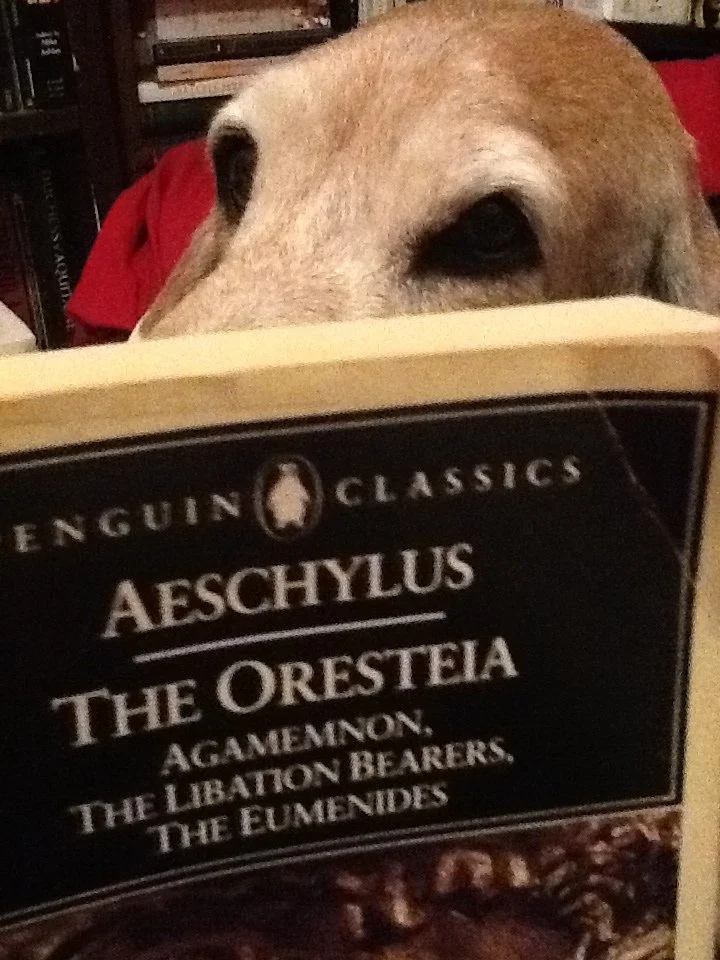

Penguins on Parade: The Oresteia!

/Some Penguin Classics, no matter how brilliantly executed, can’t help but represent the tip of the proverbial iceberg, and surely in both those respects – brilliant execution and tantalizing lost worlds – few Penguin Classics can beat the 1977 paperback of Robert Fagles’ great 1966 translation of the Oresteia by Aeschylus.

The translation is a work of surpassing beauty and immediacy, certainly the best Aeschylus in English (beating out some mighty stiff competition), ranging with assured grace from the conversational to the Olympian and back, often in the span of 50 lines. Mary Renault summarized part of its allure perfectly when she commented that it was “not intimidated by grandeur,” but there’s also a very sound sense of ordinary conversation running throughout. Probably this is understandable given the unaffected humanity of Fagles’ brief, obligatory translator’s comments:

My thanks to Aeschylus for is companionship, his rigours and his kindness. I found him a burly, eloquent ghost, with more human decency and strength than I could hope to equal.

If his translator’s apologia is brief, his actual introductory essay certainly is not: the magnificent essay “The Serpent and the Eagle” is nearly 100 pages long, and it’s so full of muscular thinking and flashes of insight that it repays any amount of re-reading, as when he offers an entirely convincing characterization of the typically slighted middle play in Aeschylus’ trilogy, The Libation Bearers:

If people are demonized in Agamemnon, here they personalize their gods. The gods remain in Delphi or Olympus, but ‘the rough work of the world is still to do’, and men who go about it find divinity in themselves. The magnificence of the opening play is muted, less because the king is gone and the work at hand is ugly than because a fresh spirit is required. The gorgeous arias yield to conversations. There is an intimacy breathing in the shadows, warm, confiding, alive. Something can be done. The Libation Bearers is a play of action.

That long opening essay is bracketed with equally long and jam-packed notes at the back of the volume, notes that gamely take up all the vexed textual and historical issues of these plays and talks about them all with a clarity so accessible you can practically hear the man in seminar. When in the Eumenides Athena says she’s not really fit to decide a case of murder, Fagles is right there to comment:

… perhaps it is simply not her province or too emotional an issue, as she suggests; but it is strange, after she had killed so many men at Troy, that she should hesitate to learn what murder means. This is Athena’s education in the post-war years, and she does not hesitate for long.

But even though you can feel yourself in the presence of translation greatness on every page of this Penguin Classic, you simultaneously can’t stop yourself from dreaming of what might have been. Aeschylus wrote over seventy plays in his career; we have only seven. Greek playwriting culture produced who knows how many hundreds or thousands of plays-in-trilogy; we have only this one. Aeschylus was revered as not only a master theatrical innovator but also a conveyer of massive power (burly ghost indeed!) – but we have no way of knowing if he considered his Oresteia to be his best work, and the numerical odds are against it. Who knows what genius was on offer in his trilogy about Jason and the voyage of the Argo? And can anybody doubt, given the very Aeschylean nature of the source material, that his Achilles trilogy would have culminated in almost unbearable drama? Those are Penguin Classics we’ll never see, fat, dense volumes that will never tempt great translators like Robert Fagles to sink years of their lives into the task of bringing them into dialogue with the present age.

It lends a melancholy shading to this particular volume, as indispensable as it is.